Films I Still Need to Watch: Face to Face, In the Presence of a Clown, Prison, Music in Darkness, It Rains on Our Love, Madame de Sade, This Can’t Happen Here, A Dream Play, The Image Makers, The Bacchae

Ingmar Bergman was one of the most consistently good directors in cinema history. For nearly sixty years, he cranked out good film after good film with a handful becoming iconic and very few being artistic failures. Diving into the Criterion box set was a long project but well worth it.

39. All These Women [1964]

Despite everything, making this zany comedy is the worst thing Ingmar Bergman ever did in his life. There is just no bite to this at all; there’s no ounce of cleverness. I will never begrudge an artist for stretching themselves, but this was as competently made of a misfire as there can be.

38. The Serpent’s Egg [1977]

I have to be honest: this seemed like a total and utter misfire. It is rare I have nothing to say about a movie, but it is bound to happen. Ingmar Bergman strayed very far from his comfort zone here. That in general is to be commended, but it did not lead to anything good. It was nice to see Glynn Turman though. This one of Bergman’s very weakest films. The one note of interest (mild interest at best) is that it can be interpreted as a Nazi-guilt film.

37. The Magic Flute [1975]

Ingmar Bergman filming this opera in a way that is visually impressive and cohesive is a true accomplishment. I just kind of don’t give a fuck about it. It reminds me of The Rite in that my reaction to it did not make sense until I read that it was originally designed for television. The Papageno in this had some real pipes on him though.

36. After the Rehearsal [1984]

Bergman’s television films are usually fascinating to a certain extent, but there is also something unsatisfying about them when you know the heights he reached in actual cinema. This was another such example; he seemed to use television as an excuse for self-indulgence. An OCD director examines his relationship with a mother/daughter pair of actresses who are inexplicably drawn to him for his brilliance and charisma or whatever. How fascinating. The technical execution almost always makes Bergman compelling; each release offers a tiny piece of the larger picture of his work; but some pieces are slighter than others and this is one of them.

Bergman’s television films are usually fascinating to a certain extent, but there is also something unsatisfying about them when you know the heights he reached in actual cinema. This was another such example; he seemed to use television as an excuse for self-indulgence. An OCD director examines his relationship with a mother/daughter pair of actresses who are inexplicably drawn to him for his brilliance and charisma or whatever. How fascinating. The technical execution almost always makes Bergman compelling; each release offers a tiny piece of the larger picture of his work; but some pieces are slighter than others and this is one of them.

35. The Rite [1969]

I have to be honest: this felt like a wank fest of a film. It has its moments where it got my attention, but overall this just felt like a misfire. I do not have much else to say. For an odd little short television film, it was fine I suppose.

34. A Ship Bound for India [1947]

Bergman’s third film is a compelling melodrama exploring familial dynamics. The father being tyrannical and made insecure by the idea of the son replacing him. The son who cannot escape the father’s shadow. The beaten down wife/protective mother. Bergman explores these relationships and displays how destructive they are. The insight Bergman offers is that despite the harm we do to others we so easily repeat past harm onto others, as the terrorized son seems to bully his once and future flame into rekindling their romance to end the film. A bleak affair.

33. The Touch [1971]

In Bergman’s first English-language film, Bibi Andersson plays a bored housewife (reductive label) who is married to Max von Sydow. She becomes infatuated with a visiting American, Elliott Gould. Andersson is longing for the feeling of independence. Gould is a reckless man who offers nothing of the sort – he has his own ways of suffocating Andersson. He only wants to take from her ultimately – in all likelihood he is also just another lost soul doing his best to feel at peace. But he is a child until the very end. He has no tools to improve himself in any way and thus would just be a new form of torture for Andersson. She longs for the passion (Sydow continuously offers none to her even in the face of her potentially leaving him) – but she eventually realizes she wants everything not merely that. It’s a slight film but enjoyable all the same.

32. Summer Interlude [1951]

A year after To Joy, Bergman again explored the idea of younger lovers being separated by death and the surviving one looking back on their lives. In this case, Marie had a summer romance with Henrik and he died at the end of the summer. She had to go through the rest of her life living with that loss. She was exploited by an older family friend. Her current relationship was undermined. It is empathetic study of loss of innocence and regret, but Bergman has explored both in more interesting ways before and after.

31. The Magician [1958]

While there is something to be said for a thematic analysis of this film from the perspective of analyzing the thin line between a charlatan and the genuine article, I cannot say I care too much about that aspect of it. Yes, this is a fine hyperbolic exploration of the idea that a vast majority of people are putting out a vision of themselves that is partially phony and partially sincere, but I really connected to this more as a hangout movie. It contains a much deeper roster of characters than most Bergmans, and I just genuinely appreciated dipping into this world for a little. If anything, I wish I could have stayed here more.

30. The Passion of Anna [1969]

In this film, Bergman focuses in on four characters who are all varying degrees of emotionally broken. The film is a mature but slight story that hammers home how impossible it is for broken people to love others properly. I was not overwhelmed with this film. It was however well-executed and was satisfying in the context of Bergman’s filmography and his work with these actors specifically.

29. Fanny and Alexander [1982]

This was the initial theatrical cut. It is impossible to watch the three hour version and not think about how much emptier it feels with the cut two-and-a-half hours. This is of course good on its own, in its own bubble. But just watch the full version and never bother with this version.

28. Scenes from a Marriage [1974]

I truly wonder how I would have responded to this film if I had not watched the six-hour miniseries version first. So much of what felt essential to the original version was that it allowed you to just sit and marinate in their relationship for almost five hours. Cutting out half of that really undercut so much of what made that deadly effective. This is feature-length version feels like a cliffnotes version in comparison.

27. To Joy [1950]

To Joy is an exploration of the tension between personal ambition and your family and relationship. Stig has ambitions related to his orchestra career despite what is likely a low ceiling on his potential. The insecurities that go along with his lack of accomplishments in his field lead to self-destruction for much of his marriage to Marta. Marta, who feels compelled to support him in so many ways is left to feel unsatisfied in many ways. The frame for this story if Stig learning about Marta’s death at the beginning of the film and then having to reflect back on a marriage full of regrets. It’s an idea that Bergman would explore a lot.

26. Shame [1968]

Shame is a rather fascinating departure from Bergman. In an imagined Swedish civil war, the film follows two former artists doing their most to remain detached from that reality. There is of course no escaping war. What does it mean to be apolitical? How meaningful is art actually when guns are involved? War can make cowards of us all, and it certainly does do that to the characters. This is a bleak film for a bleak world. War destroys the inner lives of this couple and creates a divide that feels impossible to bring back together.

25. Crisis [1946]

Bergman’s debut film is a relative stunner. The film follows an eighteen-year-old woman at a cross-roads in her life. She is experiencing the slow torture that it can be to be a young person (especially a young woman) who is trying to open herself up to experience the world. Everyone around you can often just see you as an object that fills their own holes in their lives. She is an object of desire in more ways than one. Sure, older men want her, and it is a bit creepy. But in some ways the more tragic dynamic is the older women in her life who try mould her life to fit their own needs. We claim to love people, but we so rarely are effectively able to do so. We too often take when we really need to give.

24. Port of Call [1948]

In one of Bergman’s earliest films, he dissected how women are systematically controlled and held to different standards. There is rampant slut shaming, inadequate healthcare regarding pregnancy and abortion, and the institutions of the west literally try to dictate the behavior of women. It is not a profound film or anything, but it is slick and well-made and interesting peak into what moved him as an artist early in his career. It is especially notable, as he seemed almost more open-minded at this stage of his career compared to later when he was far more perturbed by the lack of worship for almighty nuclear family.

23. Thirst [1949]

Seeing an early Bergman film is so fascinating because there are some technical aspects that feel closer to “old Hollywood” or whatever, but the themes and ideas are the ideas that Bergman always explored up until his death almost sixty years later. Every adult joins a new relationship with their own traumatic romantic history; we are not blanks. And while we may have been changed and shaped by that history, we have not necessarily “grown up” or improved upon ourselves simply by being experienced. We can still be fucked up in all sorts of new ways. If we do not commit to truly changing our behaviors and habits that undermine our relationships, we are going to continue to run over others (and ourselves) in perpetuity.

22. Brink of Life [1958]

As a childless dude, I was pretty ignorant about the impact of pregnancy on a person. The first time I was in regular contact with a pregnant person, I found it fairly jarring to witness just the tremendous physical and emotional and psychological toll it took on the person. They were never the same in many ways. I say all that to say is that very few films have really attempted to capture the pure terror that pregnancy can be in many ways – leave it to Ingmar Bergman to attempt to do just that. This is an incredibly bleak film about three women in a maternity ward essentially being tortured by the parasite growing inside them.

21. Secrets of Women [1952]

Bergman uses the conceit of a group of women waiting for their men to come home for dinner to examine what it is like for women trying to make their way and own their own lives in a patriarchal world. The film sees different generations of women going through similar but distinct struggles that reflect their own struggle to attain agency in the most healthy way when there are so many pitfalls in a male centered world. They are not at peace because their lives and actions are not what they want, but they are trying their best. Much like in some of his earlier films, Bergman seemed more preoccupied with the agency of women in a patriarchal world and less concerned as he would be in the future with his fears of the breakdown of the family.

20. A Lesson in Love [1954]

Bergman announces at the beginning that this film could have been a tragedy but instead everything works out for the characters so it turns out to be a comedy. I am curious about how sincere that was on his part, because the “happy ending” seems far more tragic than that supposed intention. I suspect it was ironic.

Regardless of the intention, a tragedy plays out on screen. A man has a great wife and children. (One of whom is openly pining to transition from their sex assigned at birth to male by the way. It was heartwarming to see it so casually included quite frankly.) He cheats repeatedly and pushes his wife away. They separate. Neither seems truly satisfied away from another. For her, her options are not better. For him, he misses the stability and comfort of marriage. And before she knows it, they end up back together at the end just as he desired. This is a lesson in love between a man and a woman – it is also as much of a warning of what can come. When you make decisions and choices that are not true to who you are, unhappiness will follow for all involved.

“We weren’t any wiser at 20, were we?”

Dreams centers around two women. A middle aged woman and a younger woman. Through their experiences over the course of a rather eventful day, we get to see the recklessness of youth and regrets of middle age. The generation gap does not matter so much though; you’re just as likely to be self-destructive and cruel, and you’re just as likely to be tossed aside if you’re a woman. But for the young, there is still the hope for tomorrow. Whereas for older women, with each passing year in this society your options get lesser and lesser. This is a beautiful and haunting film.

18. The Devil’s Eye [1960]

All These Women shows that Bergman could not do a straight comedy, but films like The Devil’s Eye shows that he could do lighter-hearted fare that was very successful. In this film, the Devil is real, and he is very concerned that women have stopped having pre-marital sex. How can hell stay in business if pre-marital sex isn’t happening??

The film presents marriage and hell as two points in a toxic cycle. The marriage trap feeds hell, but hell feeds toxic marriages. That contradiction is actually an interesting idea to examine. The Devil sending a damned lothario (not-so cleverly named Don Juan) to seduce a virgin to keep the wheels of hell spinning is actually a clever conceit to make for a fun film that examines a real dynamic. Humans’ best instincts revolve around love and looking to commit to each other. Humans’ worst instincts are connected to dishonestly satisfy our own temporary desires at the expense of others. How can we resist the urge for our worst instincts at the expense of us at our best?

17. Through a Glass Darkly [1961]

In this film, we see adult (or near-adult in one case) children suffering due to an inconsistent father. An artist father has been prioritizing his own desires and ambitions. He has abandoned his children. They are emotionally deprived. And the adult children ended up fucking each other.

Sure, this is an extreme, hyperbolic scenario, but the consequences of an adrift society are being clearly stated. The film speaks to a larger truth of the responsibility of parenthood and society to provide for those dependent on them.

16. Saraband [2003]

The final film of the iconic Ingmar Bergman’s career saw him revisit perhaps his most iconic work. Thirty years after Scenes from a Marriage, Bergman checked in on the main couple again. With 2024 eyes, that concept may not see so shocking, but I would imagine that in 2003 this felt at the very least unconventional. Bergman does not waste time repeating himself. He uses the foundation established in Scenes to explore the generational damage our destructive relationships bring. Bergman looks at how the self absorption of people in a horrific relationship and how they never recognize how they’re impacting others. In far too many cases, it is the children who suffer. And the children’s children. His unwillingness to repeat himself makes this a more-than-worthy follow-up to his classic work and send-off for his own career.

15. Hour of the Wolf [1968]

Johan and Alma live on a remote island, almost completely by themselves. They have an idyllic life – the one of fantasies in many ways. Their paradise gets ruined though once Alma starts examining what is happening on the inside of Johan’s soul. On the surface, Johan is perfectly content with his life – but as is the case for so many, he longs for the alternate realities where is he is with someone else (in this case, his gorgeous ex-girlfriend). Alma explores what is happening beneath Johan’s surface though. Doing so completely destroys the balance of their world – reality breaks. The film turns into minor horror film as Johan is finally “able to” break away from his wife by shooting her and going through an ostensibly haunted castle to finally be with his long-lost lover again. As is the case for so many, Johan destroys his present by refusing to let go of the past.

Johan and Alma live on a remote island, almost completely by themselves. They have an idyllic life – the one of fantasies in many ways. Their paradise gets ruined though once Alma starts examining what is happening on the inside of Johan’s soul. On the surface, Johan is perfectly content with his life – but as is the case for so many, he longs for the alternate realities where is he is with someone else (in this case, his gorgeous ex-girlfriend). Alma explores what is happening beneath Johan’s surface though. Doing so completely destroys the balance of their world – reality breaks. The film turns into minor horror film as Johan is finally “able to” break away from his wife by shooting her and going through an ostensibly haunted castle to finally be with his long-lost lover again. As is the case for so many, Johan destroys his present by refusing to let go of the past.

14. Cries and Whispers [1972]

Visually, this movie was like no other Bergman film that I had ever seen before. There was almost a gothic-like quality to the look of the film. The look contributes to a heightened emotional state of the characters. The film is centered around three sisters – one of whom is physically dying and two of whom are spiritually almost worst off. The other main character is the maid who is the primary caretaker of the (physically) dying one. The film then explores how much pain one’s own family can bring to someone just with their presence. There can be so much emotional harm done over the years that goes undiscussed never mind un-repaired. In contrast, non-familial relationships who come to you later in live can be far more loving and caring for someone than their own blood. And the blood relations resent such “interlopers” and see them as illegitimate. This movie spoke to me in ways I did not realize I needed to hear. One of the Bergman’s most disturbing, upsetting, and ultimately one of his best.

13. The Silence [1963]

The Silence is a rough and bleak film that focus primarily on two sisters who are traveling together but are seemingly just existentially sick of each other. There is so much unspoken resentment boiling under the surface (until it’s spoken by the end). Much like with Through a Glass Darkly, I was struck by how much the children of self-obsessed parents were suffering and adrift without the guidance, love, and support that children need to feel secure. Also like that film (and Winter Night), there is just a sense of impending doom this film that is just so skillfully done.

12. From the Life of the Marionettes [1980]

Bergman utilized a sincerely clever story idea to explore the theme he always had the most to say about: why do people who were once in love proceed to destroy each other. To get there, Bergman starts the film off with a disturbing scene of the main character, Peter, murdering a prostitute. We learn Peter is married to a woman with the same name as the prostitute. Bergman takes an unconventional approach to exploring why this murder happened. He does pretty much the Citizen Kane structure with an investigator interviewing the people in Peter’s life about who he was in the hope of explaining what the hell happened – or why it happened more specifically. This non-linear structure emphasizes how confusing relationships are and how much everything that goes wrong can feel obvious only in retrospect. When you’re in a terrible relationship, your vision is foggy. Only afterward does it turn 20/20.

11. Wild Strawberries [1957]

Ingmar Bergman loves to craft a film about someone looking back at their life and examining all of their regrets. It is simply a fundamental part of being alive. While many such films from him, especially his early ones, were about young lovers separated for one reason or another, Wild Strawberries, one of his most famous and beloved films, is about getting old and looking back. A film like this examines and develops empathy for the reasons why people are the way they are and the impact their lack of dealing with it can have on others – especially their loved ones.

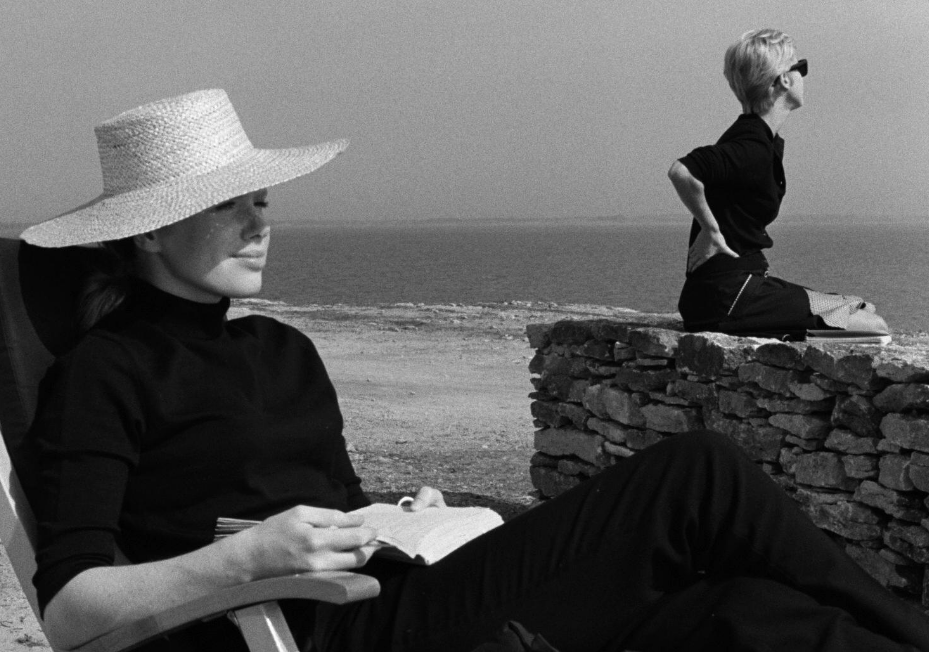

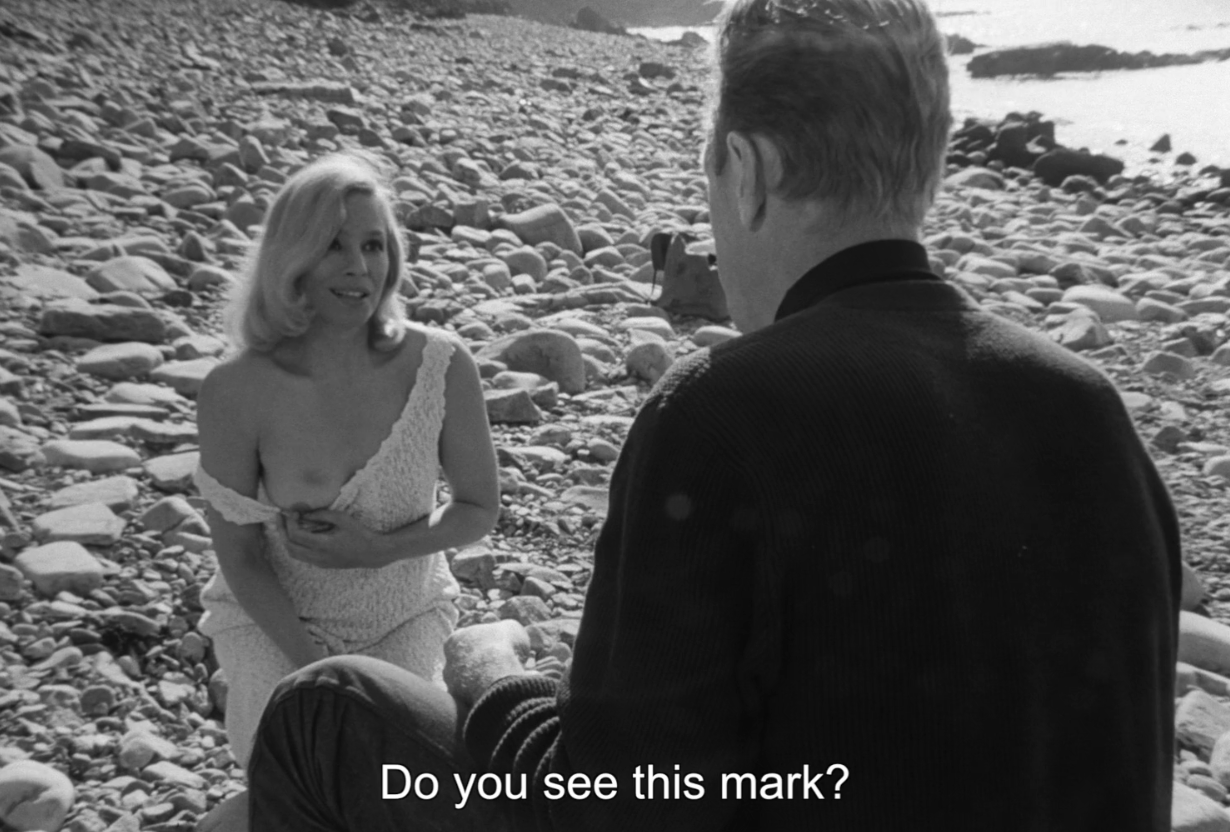

10. Persona [1966]

Persona is a film ripe for interpretation, and there are so many ways to go about it. The most obvious one to me is Bergman’s continued obsession with what constitutes a family and the fears of children growing up without parents. In this film, a woman driven insane by becoming a mother. The fear of an abandoned child drives so much of Bergman works. This looks at the other side of it though – what happens to a parent when said parent does not want that child? She disintegrates as a human being and has been rendered mute and helpless and in need of 24/7 care. It is a fascinating film, but it reveals perhaps the most reactionary exploration of family yet by Bergman. How dare this woman not want a child? It is unnatural of her.

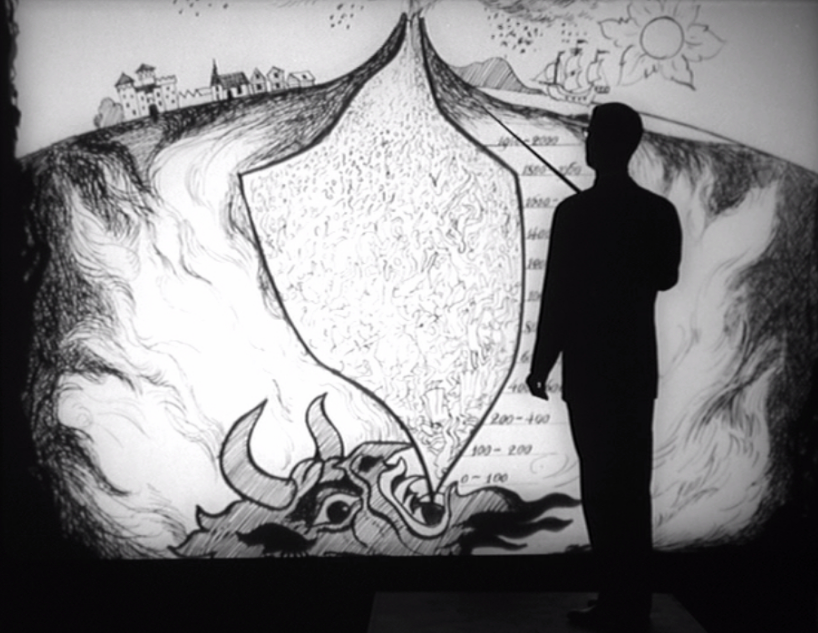

9. The Seventh Seal [1957]

The Seventh Seal is perhaps Bergman’s most infamous film with the Knight playing Death in chess a “meme” cinema moment that many people can recognize whether they have seen the film or not. In some ways though, that makes the film more interesting to look at because the film is so much more than just that aspect.

The chess game is of course significant though because it tells the audience from the jump that a great doom is coming. We are approaching the end. What can we do? What should we do? This is a familiar feeling in Bergman films. He was obsessed with a usually unseen terror on the horizon, and the impact that has. He is often preoccupied with the impact the world has on families and children in particular. That is what makes the ending of this film stand out so much as there is almost a cheerful or hopeful ending. Why? The one nuclear family in the film is spared by Death as all the other (heathen) characters are sacrificed for it.

8. Sawdust and Tinsel [1953]

I have been watching Bergman’s films in the order that the Criterion Collection box set ordered them. For some reason, this early film was placed in the second half of the collection. At first, I found this to be impressive for an early film from the future legend. But it felt slight. A cute exploration of gender roles in a goofy (circus) scenario.

Then things got interesting. It became clear that this film was not a surface level exploration of gender roles at all. The film portrayed an all-too common dynamic. The men were acting controlling and irrationally possessive. The women were fighting for autonomy and individuality. The circus owner was cheating on his wife with a circus worker. Both women slowly realize they are better off getting away from this man.

This film stands in sharp contract towards so many future Bergman films – films when he was more in control of his craft but had become far more reactionary in theme. He was so preoccupied with the threats to the nuclear family throughout so many of his films – it was downright jarring to see a film where he he sees value beyond protecting the family unit above all else.

7. Winter Light [1963]

In Winter Light, a priest is having a crisis of faith, and Bergman uses this premise to ask many questions about the role and value of religion and faith in society and one’s life. What is the value of religion and faith? Can it heal your emotional pain? Does religion just numb you to the reality of the terrors of the world? Is there value in that? Why are we so dependent on religion to keep going? Bergman knows the value of letting a film meditate on questions rather than answering them. The film explores the contradictions between acknowledging the inherent material uselessness of religion with the simultaneous necessary comfort it can provide for some. There is value in keeping going even in the face of certain doom.

6. Summer with Monika [1953]

Summer with Monika feels like Bergman’s first truly classic film. He had a firmer grasp of his visual sense, explored many of the themes that were his trademarks, and for the first time built to a devastating emotional climax.

A young, reckless love affair is one of the most intoxicating feelings in the world. It is drug that is nearly impossible to quit. And if you are not careful, it is a high that you will chase until there are dire consequences. Harry and Monika come together and have a summer of bliss. Their innocence allows them the boldness to escape their dissatisfaction with regular life. Harry is stuck in a dead-end job, and Monika is trapped in an unhappy and restricted adolescence under her parents’ thumb. These two desperately needed to escape home and experience something. And that experience was beautiful until it was washed away by the crushing tidal wave of reality.

Monika gets pregnant.

Pregnancy ruins the delusion they had been living in. Harry must get a job. Monika must care for the baby. Harry is once again stuck in a dead-end job. Monika is once again trapped and restricted. This drives her mad. She lashes out at Harry. Harry is resentful of her lashing out.

There is this one particularly terrifying moment late in the film when they arrange for a night for Monika to have all to herself. She is so excited that the audience can tell disaster must being looming. The tension only gets worse until it reaches a boiling point: Harry slaps Monika. This action destroys both of them and their relationship (such as it was) in the process.

A beautiful and haunting film, Summer with Monika is one of Bergman’s very best.

5. The Virgin Spring [1960]

The Virgin Spring is a devastating exploration of the intersection of multiple aspects of a patriarchal society that results in the all-too common utter destruction of women. This society has so many archaic conceptions of how women are “supposed” to live their lives, and it is leading to a worst world for everyone. I am also struck once again by a persistent theme in Bergman’s work of abandoned children. This happens in a variety of ways in his works and also in this film. Karen, the victim, is not properly cared for by her living parents due to these bizarre religious structures. The rapist/murderer brothers also were without parents though and eventually grew up to be monsters. This is one of Bergman’s best films.

4. Smiles of a Summer Night [1955]

When I sat down to watch this, I had not seen a Bergman film in close to twenty years. He was just someone who started to fall in the cracks after college for me. And what a reintroduction it was. The way Bergman just injects humor into what is really a ridiculous soap opera setup to capture something very true about what it can feel like to be young, be in love, be in a relationship, and hitting middle age and all together is really just the stuff of genius. I just loved it.

3. Autumn Sonata [1978]

“The mother’s injuries are to be handed down to the daughter. The mother’s failures are to be paid for by the daughter. The mother’s unhappiness is to be the daughter’s unhappiness. It’s as if the umbilical cord had never been cut.”

In one of Ingmar Bergman’s finest achievements, he teamed up with cinema’s other legendary Bergman (for the first and only time) to create a devastating examination of the deep pain that can pass from parent to child. Ingrid Bergman is a functional mentally ill woman who very clearly was never meant to have children. She did not have the tools to be good to herself while raising a child, and her wiring led to her choosing herself over and over. These continuous choices clearly had repercussions on her daughters and caused a great deal of damage. The film sits with her eldest daughter as the mental and emotional consequences are laid bare. While the film is primarily told from the POV of said daughter, one cannot help but wonder what did society do to Ingrid in her own rearing that led to her to have children she clearly never wanted to raise? What are the consequences for a society that continuously insists women only have value as breeders?

2. Fanny and Alexander [1983]

(This is the television miniseries version that was also released cinematically.)

After having seen the theatrical version close to two decades earlier, I finally went back and watched the full version. The film is a remarkable accomplishment. Bergman used elements of his life story to truly capture what it feels like to have traumatizing experiences at a child. The film shows the way our life is happening all at once in one continuous moment. People dying and going away does not end our connection to them. We are haunted by the past. We are shaped by the past. Moving forward in life is not a simple straight line process. In this extended version, we really get to marinade into the full family and get the feel for so many different branches of this family. It is an incredibly rich experience, and one of Bergman’s best films.

1. Scenes from a Marriage [1973]

“Do you believe two people can spend a lifetime together?”

I am going to make an exception I hate to make. While technically Scenes from a Marriage was first released as a miniseries, I consider it a five-hour film. I am a hypocrite, and I am not even going to pretend to justify this inconsistency. This film feels like the definitive statement on the unhappy cishet relationship. The first scene is the key: the couple is being interviewed about their life together and their separate lives in general. The man is full of self-assurance and a fairly false sense of bravado about all the wonderful things in his life and their life together. The woman has nothing to say about her life other than that she is a “wife” and a “mother.” None of the glaring concerns about this harsh juxtaposition seem to register with either of them though in a meaningful way. It is a clear sign that this is an unhappy marriage that needs some work to get it on track. But instead they are unwilling to accept how terrible it is which makes the rest of the events that unfold all the more tragic yet predictable. Of course, the man reveals he has been cheating on her and leaving the marriage. Of course, the new romance does not work out and he comes crawling back. Of course, the woman only starts to find her sense of self once he leaves. And of course, these two broken people cannot help but start up again and feel “happy” despite both being in new marriages. They could not heal themselves and now they are hurting brand new people. This is a beautiful and empathetic exploration of an all-too-common dynamic. It is also one of the best films of all time.