Willow Catelyn Maclay and Caden Mark Gardner recently published their book, Corpses, Fools and Monsters: The History and Future of Transness in Cinema. First of all, it is a fantastic book and you should buy it. Secondly, one of the films that they discussed that stood out to me the most was Nikolai Ursin’s Behind Every Good Man.

Maclay and Gardner explain in their book: “Ursin…shot a hybrid of documentary and scripted fiction to depict the everyday life of a trans woman…[the film] is a stunning eight-minute document focusing on a trans woman of color that, in 2022, was added to the National Film Registry in the United States.”

Reading that, I could not help but feel like this was a truly historic text that needed to be watched as soon as possible. Thankfully, Maclay and Gardner also explained that the film had recently be restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, so it was rather easy to find the film and watch it myself.

I was so blown away by the film that I wanted to attempt to write something about it. It is not hard to understand why this film stands out to so many when they watch it. As the UCLA Archive wrote, “In strong contrast to the stereotypically negative and hostile depictions of transgender persons as seen through the lens of Hollywood at the time, the subject of Ursin’s independent film is rendered as stable, hopeful and well-adjusted.”

And while the what the film showed and conveyed is as significant and important as the brief summary states, it was the how the film was shot that particularly struck me.

We are introduced to the woman as she is shopping in a clothing store. She is looking through different dresses, deliberately going through each one. We see her trying dresses on in the mirror. There is a confidence and self-assuredness to her movements and looking into the mirror.

While she is doing this, we hear her say in the narration, “I’d like to live a respectable life, that’s for sure. I’d like to live a happy life.” The film portrays her desires sincerely. There is no hint of anything but empathy from the camera.

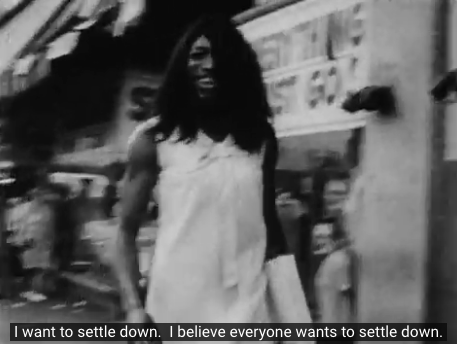

We move on to watching the woman walk the streets. You can see her radiant smile as her narration continues, “I want to settle down. I believe everyone wants to settle down.” There is a hopefulness in her voice. There is not fear or dread; her desire is not just conveyed sincerely but also with the belief from her that this desire is possible.

We then see a mixture of men staring at her, one by one, as she walks the streets. I say mixture because as best as I can tell on repeated viewings, there are a variety of reactions to her as she walks. Some of the faces imply generic cat calling or perhaps something more generally considered polite. Other faces potentially convey something more negative. “Gawking” as Gardner and Maclay wrote is a fair word as well. What stands out though is the woman’s reaction. She is either smiling (or perhaps laughing them off) or relatively neutral in her response. Are the men interested in her? Is she just using happiness as a defense mechanism? Or is she happy for the attention?

The ambiguity in how we should respond to this scene seems like a honest capturing of the situation. Perhaps though as a cishet man this sequence seems just less potentially dangerous to me. Also of note during this sequence is that her narration and continues, and she actually explains what she is looking for in a man. Not just any old man who looks at her or hits on her will do. She can envision what she is looking for in a man. She does not want to settle for anything in the negative sense.

The montage of men ends with the woman exchanging glances with one particular man. If his interest in her was in doubt, it became clear he wished to pursue her when he shakes off his own friend to avoid the third wheel dynamic. The woman and this man then proceed to walk off together, hand in hand. The film seems to be saying that the woman’s desire to settle down and find the right man is truly possible. Something about this man’s eyes and gaze feels like he sees her as a human and not a fetishized object. He is attracted to her and interested in seeing her again. That sense is furthered by the soundtrack as Dionne Warwick’s “Reach Out for Me” plays over their initial hang where it seems their mutual interest is confirmed. The woman is so enchanted that she loses track of time and misses her bus.

We then get a montage of the woman getting ready for her date with the man. This sequence of images is juxtaposed with her narration of her telling a story of her using a public restroom. She was using a men’s room by choice, and it led to a cop coming in and removing her. She then recounts how the cops ran her name and determined that there were no warrants. So they proceeded to make small talk together, and one of the cops told her, “It’s too bad you’re a boy, because you’re a real knockout.”

This narration is paired with images of her getting dressed and doing her makeup and hair for her date tonight. Her process is direct. There are no pained looks in the mirror. She is getting dressed and putting the care into her appearance the way most do for a first date. She seems at peace with her body from my eyes.

Dusty Springfield’s “Wishin’ and Hopin'” plays on and off in the background. Dusty explains how to get and keep your man. The woman at the same time is putting the most precise care into her date and all the facets of it between her look and the meal setup with candles and everything. This woman is trying to get her man to achieve that “respectable” and “happy” life that she wants.

Also of note in the date preparation sequence are the shots in passing of what seems to be a childhood photo. It is reasonable to assume that this is the young woman as a child with her mother. We get no further information about her life before these eight minutes captured on film, but it is a reminder that she has lived a life with a family. What are those familial connections like now? Her life does seem isolated. Does she have any family support of any kind? Or this just a reminder that like everyone else in the world, this woman did not just simple appear one day out of nowhere.

Also of note in the date preparation sequence are the shots in passing of what seems to be a childhood photo. It is reasonable to assume that this is the young woman as a child with her mother. We get no further information about her life before these eight minutes captured on film, but it is a reminder that she has lived a life with a family. What are those familial connections like now? Her life does seem isolated. Does she have any family support of any kind? Or this just a reminder that like everyone else in the world, this woman did not just simple appear one day out of nowhere.

The film closes on a sequence of the woman looking out the window for any sign of her man and then trying to be patient and just wait on the couch. She is waiting for that man who will give her the happy and respectable life. She tries to distract herself by putting on the record “I’ll Turn to Stone” by The Supremes. She tries to dance along, but she immediately gives out. She cannot force herself to pretend to be happy right now. She thought she may have found someone special, and he did not show up. She blows out the candles. She sits down.

As Gardner and Maclay write, “Will a man come into her space and stay there? Will he ever come?” Why did the man not show up? Will any man ever show up? Will she get the love and life she wants? One cannot help but think of her story about the cops with one of them saying it’s a shame she’s a boy because she’s so attractive. Is she doomed to always have flames of desire extinguished? Is this tragic finale destined to be permanent?

“Taking love away, I’ll be lost and alone. No reason for living, all purpose would be gone. Without you there, for my eyes to behold, my life would be empty, my heart would grow cold. If you take your love from me, I’ll turn to stone. Turn to stone. If your love I couldn’t call my own, I’ll turn to stone. Turn to stone. When I think of love, I think of you and me. When I think of happiness, I think of us too.” – The Supremes

Please buy Corpses, Fools and Monsters: The History and Future of Transness in Cinema. The book is fantastic.