13. The Stranger [1946]

Welles used his immense skill to craft this sleek noir that contains one of the most reliable stories in all of film: hunting down Nazis. On top of being a crisply edited and beautiful looking film, Welles also does just a fantastic job in the titular role. If there is a defining quality to Welles ON the screen it is that he just feels like the center of the universe. He is the sun, and the everything lives and dies based on him. Only a handful of actors have ever been able to convincingly do that perpetually, but he was always one of them. He also has that terrifying ability to be utterly convincing even when he is blatantly lying. For some reason, you want to believe him. All of this makes for an utterly compelling film.

12. The Lady from Shanghai [1947]

“When I start out to make a fool of myself, there’s very little can stop me.”

Shanghai works so well because of the POV. Right from the jump Welles’ narration admits that he is a fucking idiot and metaphorically stepped on the rake over and over again. This along with the absolutely insane decision to have Welles’ Michael O’Hara to not just Irish but also have an Irish brogue makes for a truly chaotic dynamic. There is a sincerity to O’Hara in how much he dives into a situation that he knows he cannot fully control. It makes the fact that he is an idiot and easily outwitted several times more enjoyable and less annoying. Most of us are just fucking numbskulls who cannot help but jump into the deep end without any sure path to escape.

11. Othello [1951]

I am not sure why blackface was ever a thing that seemed okay let alone why it was still so socially acceptable at this time. That issue here almost serves as a metaphor for why this version of Othello does not hit me as hard as others do and possibly why it seems like distinctly the weakest Welles Shakespeare. Welles feels out of place here in ways more than the black paint covering his visage. Othello has always been one of the miss-titled Shakespeares as it is really about Iago. In many ways, Othello is my favorite Shakespeare for precisely that reason. Iago is a fascinating villain in a great many ways, but Welles has never really been outwardly fascinated by his kind of evil nor the pitiful tragedy of Othello types. Welles always gravitated to titan-like figures and the tragedy of humanity. That is not really at work here, and the film comes across as a beautifully technically made mismatch of auteur and story.

10. The Trial [1962]

While there are many striking things about how Welles shot The Trial, the beauty of this film for me lies in the casting of Anthony Perkins. Perkins has a masterful ability to kind of make himself shrink into himself to make himself completely outmatched by the situation he is in. As the victim of a mysterious prosecution, that way he carries himself is invaluable for conveying the stakes of the situation. Once this system sets its sights on you, it can be impossible to get free. Perkins moves like he is perpetually locked up in a strait jacket and makes it seem like he is already imprisoned.

Simultaneously though, Perkins always works like he is keeping some key cards close to the vest but also with sincere innocence. There is a mystery behind his eyes that makes you doubt that you know everything going on with him Yes, on one level you want to take the film on the level, but the story is so disorienting in some ways that you start to doubt that you understand what is happening. Perkins is the key for that. He sucks you completely in and makes you want to know what the fuck is going on.

9. Macbeth [1948]

The way Orson Welles manages to center the failure of Macbeth as a human here is incredible. Something about this play has always felt a little flat on the page, but Welles makes everything pop and intense from beginning to end. The way he managed to create just a smidge of empathy for his Macbeth early on sucks you into this character that can often feel an object instead of the subject in the story. The way that power just slowly but loudly drives him madder and madder creates a sense of terror in the film. It’s like there is a monster lurking around the corner waiting to destroy him at every turn, The driving emotion of Macbeth is fear, and Welles just radiates fear at all times.

The way Orson Welles manages to center the failure of Macbeth as a human here is incredible. Something about this play has always felt a little flat on the page, but Welles makes everything pop and intense from beginning to end. The way he managed to create just a smidge of empathy for his Macbeth early on sucks you into this character that can often feel an object instead of the subject in the story. The way that power just slowly but loudly drives him madder and madder creates a sense of terror in the film. It’s like there is a monster lurking around the corner waiting to destroy him at every turn, The driving emotion of Macbeth is fear, and Welles just radiates fear at all times.

8. The Immortal Story [1968]

Much like a few years later when he started making The Other Side of the Wind, Welles seemed to be drawn to massive figures towards the end of their lives. It was as if he was telling smaller scale stories about the final chapter of people like Charles Foster Kane instead of looking at their entire lives. As their times are coming to an end, they are looking to establish their dominance and control what they can. Their fiefdoms are crumbling. But they will do what they can to have to prove that they still can muster what remains of them to display a sense of “superiority” in whatever way they deem possible/necessary. Like Jake Hannaford in The Other Side of the Wind, Mr. Charles Clay comes to the end of his journey in this film seeing how meaningless their lives and shallow their attempts at reestablishing their power was.

7. Mr. Arkadin [1955]

“I knew what I wanted. That’s the difference between us. In this world there are those who give and those who ask. Those who do not care to give; those who do not dare to ask. You dared. But you were never quite sure what you were asking for.”

Much like he would later do with The Other Side of the Wind, Orson Welles uses Mr. Arkadin to tackle similar ideas and structures to Citizen Kane. In fact, one could even very reductively say this film in particular is a “Dark & Gritty” Citizen Kane. Someone is investigated a mysterious rich, larger than life, tycoon. Said tycoon is charming yet has participated in quite the morbid activities in his time yet there is a somber regret to this tycoon on some level.

While Citizen Kane is capable of capturing the imaginations of the masses on some level, Arkadin is stripped of any of its romanticism. All that left is the ugly truth; the underbelly that Kane always kept covered up. These men that run the world are monsters. It is so very tempting to search for explanations of how they came to be and to look for reasons to understand them now and empathize with their regrets. But there is nothing there. Just slimy filth.

6. Chimes at Midnight [1966]

The adaptation of portions of five of Shakespeare’s plays to develop a Falstaff centered story is one of Welles’ greatest accomplishments and captures much of his natural genius and his generational talent for pushing himself. Falstaff captures so many of the big ideas that Welles biggest works often either dance around or tackle head on. Falstaff is a rejection of the ruling elite and their value in many ways, and his fall from grace with the prince and future king captures the tragedy of the world we have built.

Enough about that shit. Let’s focus on the murking. It is pretty amazing how much you can always see Welles pushing himself in all of his films, and he does so again here with the big battle scene here. The sequence is just fucking insane, and is so much better than many (if not most) big battle scenes you see in major films today. While I could not consider myself an authority on big battle scenes in all of world cinema at this point in time, it does seem like it was way more chaotic, violent, and gnarly than my perception of big battle scenes from around this time period.

There is a sense of danger. It feels like everyone is going to die, and that there is not much you can do about it as a soldier because it is simply that chaotic. The quick cuts managed to make it seem like the scope of the battle was quite big despite the presumed limited resources to film it. And despite not being able to recognize any characters in the sequence, you are emotionally invested in it due to the factors described above. Just remarkable stuff.

5. The Magnificent Ambersons [1942]

“There aren’t any old times. When times are gone, they’re not old, they’re dead. There aren’t any times but new times.”

“At twenty-one or twenty-two so many things appear solid and permanent and terrible which forty sees are nothing but disappearing miasma. Forty can’t tell twenty about this; twenty can find out only by getting to be forty.”

Much like Elaine May’s A New Leaf, it is absolutely tragic that this film was taken from Welles in post-production. And also like A New Leaf, the film remains brilliant all the same.

Watching as an adult I cannot help but feel a great deal of empathy for one George Amberson Minafer. While he is a man of remarkable privilege, he is the lone character in his world that understands that when you look around and really see the world as it truly is, there is just something truly fundamentally wrong. He has no way of doing anything about and no skills or knowledge to help himself confront it or cope with it. But he gets that something is very, very wrong.

Everybody else in the Ambersons just accepts the world as it is or deludes themselves into thinking everything is fine. George’s inability to deal with the status quo causes him to wreak havoc on those around him, and it is just so sad. How do we just run over the ones we love?

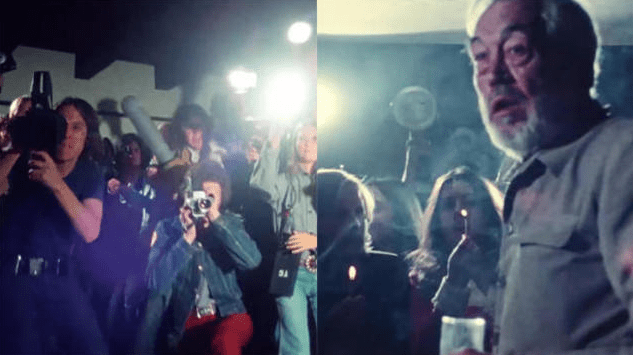

4. The Other Side of the Wind [2018]

Orson Welles made a film in the 70s that was left unfinished for forty years, and then when it was finally released in 2018 it still managed to come off as cutting edge. While the form in which the film is told is utterly fascinating, I find myself still most drawn, much like with Citizen Kane, to the immense characterization of the central character.

Jake Hannaford is at the end of his journey. At the end of the arc. Despite all of his charisma and his larger than life personality, he is finally out of tricks and at the end of his rope. His last film – his comeback film – does not have the money to finish it. As things get progressively more and more bleak, Hannaford starts to deteriorate.

With each passing moment, the film gets more and more chaotic. The film gets more and more inscrutable moment to moment. Until finally, Hannaford’s life fully goes off the tracks, crashes, and burns down. If we never see anything else Welles made, we can rest easy knowing he was still great until the end.

3. F for Fake [1973]

It is amazing that Orson Welles spent his final years making movies that were still pushing the form in new directions. Never one to settle into habits or routines on screen for all that long, Welles uses the story of the infamous art forger, Elmyr de Hory, as a means of exploring the meaning of art and the concept of “authenticity.” In many ways, this is Welles’ most fascinating work. It’s more of a cinematic essay rather than a documentary or dramatic film. The way he probes the value of what he has spent his life doing with total sincerity is quite frankly remarkable. He also managed to use this film to do many horny shots of his girlfriend, Oja Kodar. Good for her. Good for him. Good for them.

2. Touch of Evil [1958]

“They always believe me.”

Touch of Evil is just a marvelous exploration and ultimately a takedown of a classic cop archetype – Orson Welles plays the tortured cop who does what he has to do to put bad guys behind bars. Welles has been trying to stay sober and has been successful for twelve years until the case in the film. He is a widower whose wife was murdered via strangulation, and that murderer was ” the last killer that ever got out of my hands.” He is stripped of all of his glamour. He is made to look monstrous. He spews venom. His self-absorption is shown to be only that and nothing worth forgiving. All of his actions come back to selfish desires. And then at the last second, when you think there is nothing redeemable about this man, it is revealed that the person he framed for the murder at the center of this film apparently sincerely confessed to the crime. It is a moment that does not forgive Welles’ character but instead points to how tragic he was. He was as good of a detective as people said. That means he had skills where he could genuinely help people. Instead, he was the devil.

1. Citizen Kane [1941]

“I see. It’s you this is being done to. It’s not me at all.”

I have not read every word worth reading about Citizen Kane, but I cannot imagine I have anything original or even noteworthy to say. What struck me most on my latest viewing though is just how remarkable the characterization of Charles Kane is executed. It is both sweeping and intimate. Empathetic and unflinching.

Welles crafted a larger than life man who was equal parts capable of great kindness and cruelty, of pettiness and ambition. The way the journalist investigating him manages to take all of this information in and barely makes any connections or develops any understanding of who Kane was and who he continues to be in death was profoundly sad.

The most poignant part of the Kane characterization comes from how much he was set up for failure. He was an incredibly ambitious man with near unlimited resources who clearly sought to do great things for the people of the country. But coming from a position of wealth blinded him and prevented him from doing good work for the people. Wealth is poison in a capitalist country and distorts your humanity.

The Rise and Fall of Charles Foster Kane captures so much about what is so sad about being alive. Everything else the film may be, at its core, it simply is masterful just for the beautiful human story that it is.